Censorship and Celebrities–The Crazy Case of Confidential Magazine

Imagine, for a moment, that you are a famous movie star in the 1950s–let’s say you are Clark Gable (or Marilyn Monroe if you would rather identify with her). You are a product of the studio star system, which means that you were “discovered”, molded, groomed, and protected by your studio. If you got into any problems outside the studio (impregnated a co-star, attacked someone, had an indiscreet affair while married), the studio’s “fixers” were deployed in full force. Policeman/wait staff/any others affected were discreetly paid off, the affected person or persons were paid off, and the star walked away from the incident with no one the wiser. That is, until Confidential came along.

Imagine, for a moment, that you are a famous movie star in the 1950s–let’s say you are Clark Gable (or Marilyn Monroe if you would rather identify with her). You are a product of the studio star system, which means that you were “discovered”, molded, groomed, and protected by your studio. If you got into any problems outside the studio (impregnated a co-star, attacked someone, had an indiscreet affair while married), the studio’s “fixers” were deployed in full force. Policeman/wait staff/any others affected were discreetly paid off, the affected person or persons were paid off, and the star walked away from the incident with no one the wiser. That is, until Confidential came along.

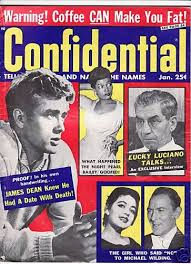

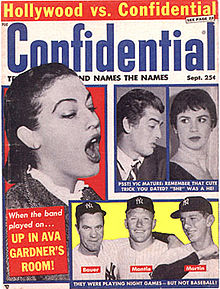

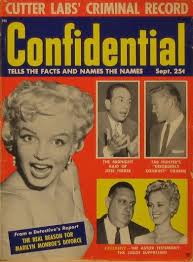

The controversial magazine Confidential was published in 1952 by Robert Harrison, and it was like a bomb went off in the movie industry. No longer content to stick to staid stories censored and often entirely constructed by the studios, Confidential wanted to expose the “real lives” of the stars–even if it meant angering studios and the stars themselves. A popular topic was Marilyn Monroe, whose difficulties in her married life to Joe Dimaggio was the subject of much public speculation. But every star was subject to the scrutiny of the magazine, and couldn’t hide from the magazine–their journalists (or those tipping them off) were always watching. In moves that inspired the tactics of paparazzo everywhere, Confidential would pay various service industry workers and civil servants to give them “tips” and “news” about stars. Bellmen could now tell the magazine reporters (for a price, of course) whom had checked in to a hotel with whom, and policemen sometimes disclosed fights or other near felonies initiated by or involving celebrities. It was a great deal, and Confidential flourished, despite being sued several times. But that was about to change.

Fed up with what they claimed was slander and libel, powerful Hollywood figures convinced the attorney general to press charges against the magazine. But that wasn’t the part of the story that interests people–it’s the fact that Harrison’s defense attorney tried to subpoena 200 stars (the subjects of the various scandalous articles in the magazine) to attempt to pry the truth out of them. Obviously, if it was proven that they were actually doing what the articles said they were doing, there were no grounds for libel because it was the truth.

Here’s where it gets amusing–trying to avoid the subpoenas, stars fled from California. Obviously, they didn’t want to admit to their scandalous activities. Some of them succeeded in “getting out of town”–others weren’t so lucky and had to testify. Stars like Maureen O’ Hara and Dorothy Dandridge were present and were asked questions on the stand. The conclusion was less than scandalous, as it was declared a mistrial. But the damage was done. After being forced to pay a fine after the second trial and not focus on Hollywood, Harrison settled other suits and tried to take the magazine in a new direction. It didn’t work. Although the magazine itself lasted until the late 70s, Harrison was gone by the late 50s, presumably selling it to another publisher.

But what the trial and the magazine illuminated was the pesky aspect of “free speech”, in that fan magazines (now often called “gossip rags”), by using less than direct language and leading the readers to “reach their own conclusions”, can ruin reputations. After the ’50s and the reign of Confidential, celebrity news started becoming more about the star’s shortcomings and dramas in their personal lives, no longer holding them up in solidarity with the studio system. After all, the studio system was crumbling by the late fifties anyway, and soon stars would be “independent”, no longer signed by and protected by studios. It’s an interesting idea to consider that once, celebrities were protected and upheld as idols while now, using their rights to free speech, magazines and blogs can publish snarky, scandalous, and sometimes outrageous claims about celebrities without much damage. Paparazzo can go to great lengths to get photographs. TMZ can record mishaps on camera and publish them on their site. However, while there are lawsuits against these outlets, it is not as big a deal nor as shocking as it once was. It was all due to Confidential that direction of celebrity and entertainment journalism changed forever.

-C

References: http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/confidential/confidentialaccount.html

All photos found on Google Images.